Be Loud

In addition to skating, I coach for our junior roller derby team. Each fall, we welcome another group of kids who will follow a tried-and-true curriculum for learning derby or in some case for learning how to keep their little wheels under their wobbly little legs at all. Interestingly, the skill I am writing about today isn’t the first lesson (get low) or the second (fall small), or even the third (stopping safely), fourth (find a friend), or fifth (embrace the suck). But just because it isn’t the first thing I teach about after we lace up our skates doesn’t mean ‘being loud’ isn’t critically important.

“Children should be seen and not heard.”

Or so the old saying goes…

Children are used to being told to be quiet. In classrooms, in libraries, in museums, in stores, in theaters, in churches, and just about any other indoor space, ‘hush’ curtly hissed by an adult is something nearly every child, and former child, has experienced at least once. We even make ‘shushing’ sounds to calm and quiet a crying baby. Our western society seems to place high value on the children who sit complacently, focus diligently, and don’t make a fuss. And when these well behaved children are rewarded with adult attention and validation, they learn this lesson quickly. Be quiet.

Learning associations like this is considered a foundational neurobiological feature. The ability to learn, to apply past knowledge in a current situation, is evolutionarily conserved (it is present in a wild variety of species) and key to survival. Early theorists described two basic forms of learning: classical and operant conditioning.

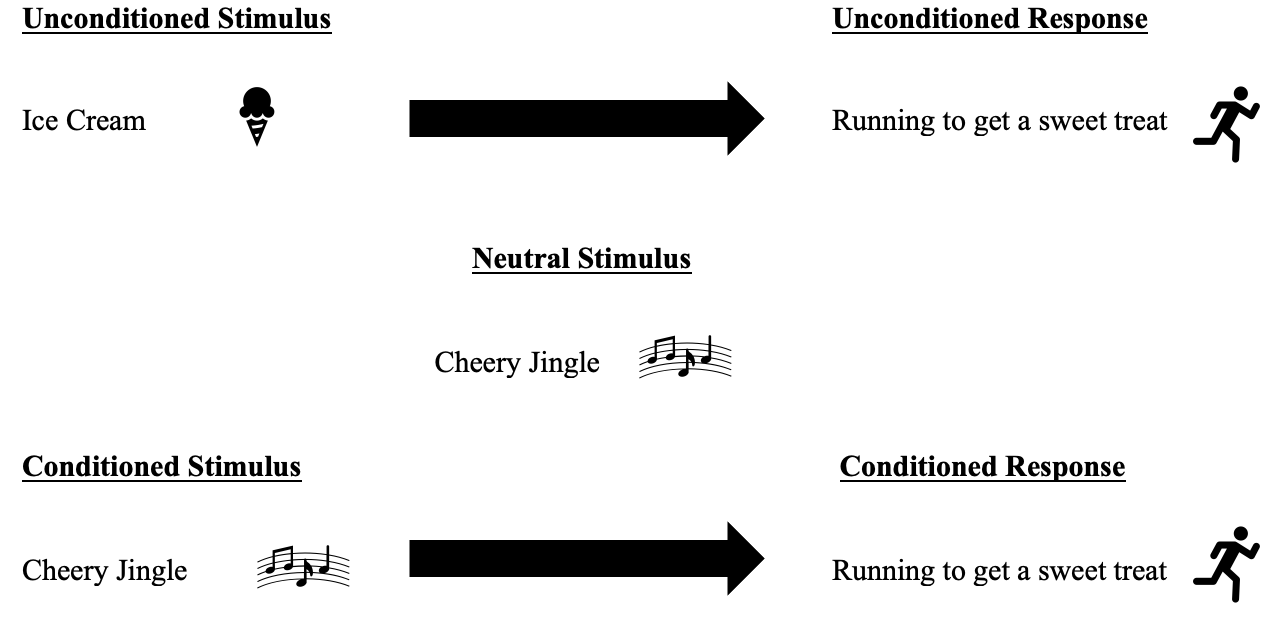

In classical conditioning, a neutral stimulus, or rather something we experience that doesn’t elicit a response from us normally, becomes associated with a meaningful (unconditioned) stimulus, something that does elicit a response from us on its own. After enough times in which these two stimuli are paired together (sometimes referred to as trials), eventually the neutral stimulus is capable of triggering a similar response that the meaningful stimulus always did.

For example, kids won’t do much in response to the sound of an old out-of-tune jingle (neutral stimulus) yet they don’t have to be trained to come running (unconditioned response) if you yell ‘ice cream’ (unconditioned stimulus)*. But just like Pavlov demonstrated in his experiments with dogs and kibble and bells, it doesn’t take children many hot summer afternoons to associate neutral signals of a slow moving truck rolling down the street playing a cheery tune (now considered the conditioned stimulus as pairings take place across time) with an understanding and excitement that they are about to get a sweet treat, which now triggers a ‘bolting outside’ (conditioned) response.

*Note, this is actually not quite true in that first, for the ‘come running’ action to be an unconditioned response, young kids have to learn to associate the term ‘ice cream’ with the taste of cool, creamy, sweet deliciousness, something any parent will attest that they do in very few trials

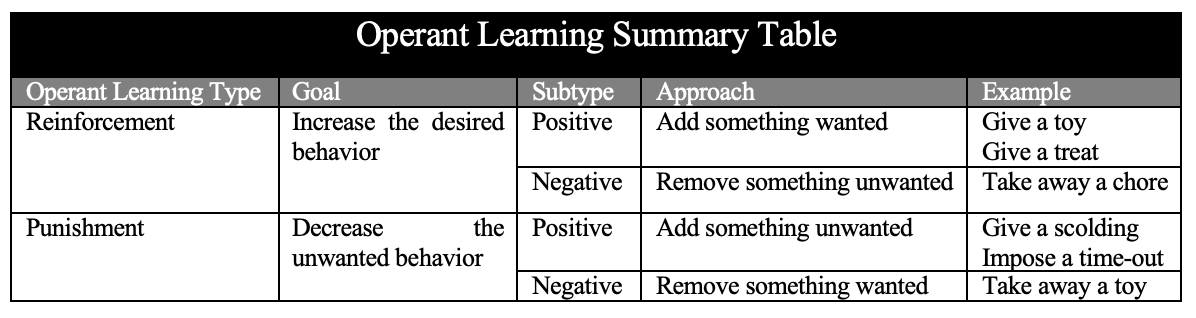

Operant conditioning, developed by B.F. Skinner, is another foundational learning paradigm however this theory involves learning associations through rewards and punishments, which strengthen or weaken voluntary behaviors. Punishments are fairly straightforward in that they associate a behavior with an undesired consequence. This can occur either through the addition of an unpleasant experience (e.g. the dreaded time-out) or through the removal of something enjoyable (e.g. taking away television privileges). Regardless of the approach, the use of punishments is designed to reduce the frequency or intensity of a certain behavior.

Rewards, or reinforcements, also come in two flavors, positive and negative. For example (see table below), encouraging a child to eat their vegetables with the promise of dessert is using positive reinforcement to promote healthy eating behaviors. However healthy eating behavior can also be encouraged through the use of negative reinforcement for example by a parent promising to lessen or remove an experience the child finds unpleasant, such as the requirement they complete a pesky chore like washing dishes. And here, regardless of the approach the use of reinforcement is designed to increase the frequency or intensity of a certain behavior.

As a boisterous, outgoing, opinionated, and distracted child, I was constantly being shhhh’d and scolded by adults for not fitting into this silent child mold, for being noisy, for being fidgety, for being disruptive. This conditioning had a profound effect on my developing sense of self. It taught me quiet my voice, to silence myself, to inhibit my reactions, and to make myself small if I wanted to fit in, to be accepted, to be considered a ‘good’ kid. And when my young and neurodivergent brain meant I couldn’t do these things well, the disapproval that came with those failures taught me to feel shame.

This message has also been reinforced and perpetuated in adulthood as some of the people in my life have attempted to silence and subdue the woman I grew up to be. Sometimes it happens in the workplace, when a colleague speaks over me or takes credit for my ideas. Sometimes it happens in relationships, when I’ve contorted myself or compromised my values to appease another. Sometimes it happens in the world beyond; given the magnitude of the #metoo movement, I am not alone in the experience of feeling silenced when there was something important to say. Thankfully when I found it (and my voice, again) in my mid-30s, derby gave me, a grown ass adult, permission to be vocal.

A derby bout is a loud, chaotic place. There are the tweets of the refs’ whistles, the calls from the bench coaches, the booming announcer, the crashes of protective padding, and the grunts of the skaters as they take hits, the crowds cheering....all of which echo through the rinks, courts, and warehouses that host these counter-culture clashes. And amidst all this noise, there is a lot happening on the track. The jammer coming around the turn, the blocker barreling in to clear the line, the skater who just fell, the player called out for a penalty… all of this has to be communicated to each of the teammates working together to get through the jam. Being loud is the only way to be heard over all the noise.

That’s why I start teaching this skill to our junior derby kids first, before getting low, before falling small, before we even put on skates! I start this lesson during introductions by loudly and proudly projecting my derby name, pronouns, and how long I have been skating over top of the many large whooshing fans inadequately cooling our hot warehouse. In so doing, I model the behavior I encourage and expect, granting them permission to be as loud too.

Invariably, these small humans are more timid, sharing their name in, at best, a normal ‘indoor’ volume. More often, they speak softly, sometimes at only a whisper. It often takes a few practices for this permission to sink in, for this generational cycle to begin to break. But like any conditioned response, being quiet can be unlearned, extinguished, and replaced with a new behavior, in this case the sounds of childrens’ shouts. And because learning curves are closely related to reinforcement schedules (the ratio of learned behavior displayed to the reinforcer/punishment given to teach the information), I positively reinforce loudness with lots of encouragement almost every time I can so that kids acquire this skill as quickly as possible. So as the season goes on and they grow louder by the day, it brings me such pride to hear these small humans find their volume knob and crank it to max, knowing that it will serve them on track and beyond.

“‘Children should be seen and not heard’ is an outdated adage that doesn’t apply to roller derby. Use your outside voices and be loud! ”

Sources:

Carlson, NR. Foundations of Physiological Psychology, 5th Edition. Pearson, Boston 2002